What would it take for you to stop reading an article, news item, or story?

Are there certain red flags, journalistic or stylistic, that are deal breakers for you that subconsciously or consciously break a standard of quality so much that you don’t see it as a credible use of your time, no matter what they have to say?

For some, it’s spelling or grammatical errors. For some, it’s certain trigger words that indicate bias.

For someone I recently spoke with, it was adjectives.

“I stop reading as soon as I see an adjective,” they said.

Exaggeration? Probably. But the point they were making was this: when it comes to news and information, I don’t want anything but the facts.

Anything other than what literally happened is conjecture and editorial, and I don’t need that to make up my mind about said event.

It’s an approach that I think many of us say we aspire to, at least in terms of being able to make up our own minds about issues based on just the facts given.

But is it what we really want?

For the record, there have been 15 adjectives used so far in this post.

In our ecosystem listening sessions, from voting advocacy groups, to Farm Show goers, to young people in high school classrooms, it was a common refrain that people:

- Want fact-based information

- Are tired of bias and spin, perceived or otherwise, and

- Are inundated with, as a peer in the space said recently, a “cacophony of content” that makes it hard to satisfy the first two things, especially since everyone is more busy than ever.

As we noted in our Ecosystem Report, one of the main results of these things is tuning out and ignoring news, especially at a local level.

The issue is, when people say they want just the facts, they’re also implying that they already have the tools necessary to interpret what they mean, whether that’s cultural context, subject knowledge, or what the results of those facts would mean for future events.

As I’ve already hypothesized, when all we have to help interpret ‘just the facts’ is our worldview, we can end up either unintentionally narrowing our beliefs, or cutting ourselves off from new possibilities.

Relying on just the facts sounds like a fool-proof way to consume news and information, but it also de facto says “I’m going to use my worldview to understand this”.

The problem is, we can’t agree on facts anymore. And we increasingly don’t trust the sources of these facts, even if we agree with them.

A Gallup/Knight poll in 2020 found that “nearly half (46%) of all Americans think the media is very biased. Fifty-seven percent say their own news sources are biased, and 69% are concerned about bias in the news others are getting. Nine percent — driven largely by conservatives — say distrusted media are trying to ruin the country”

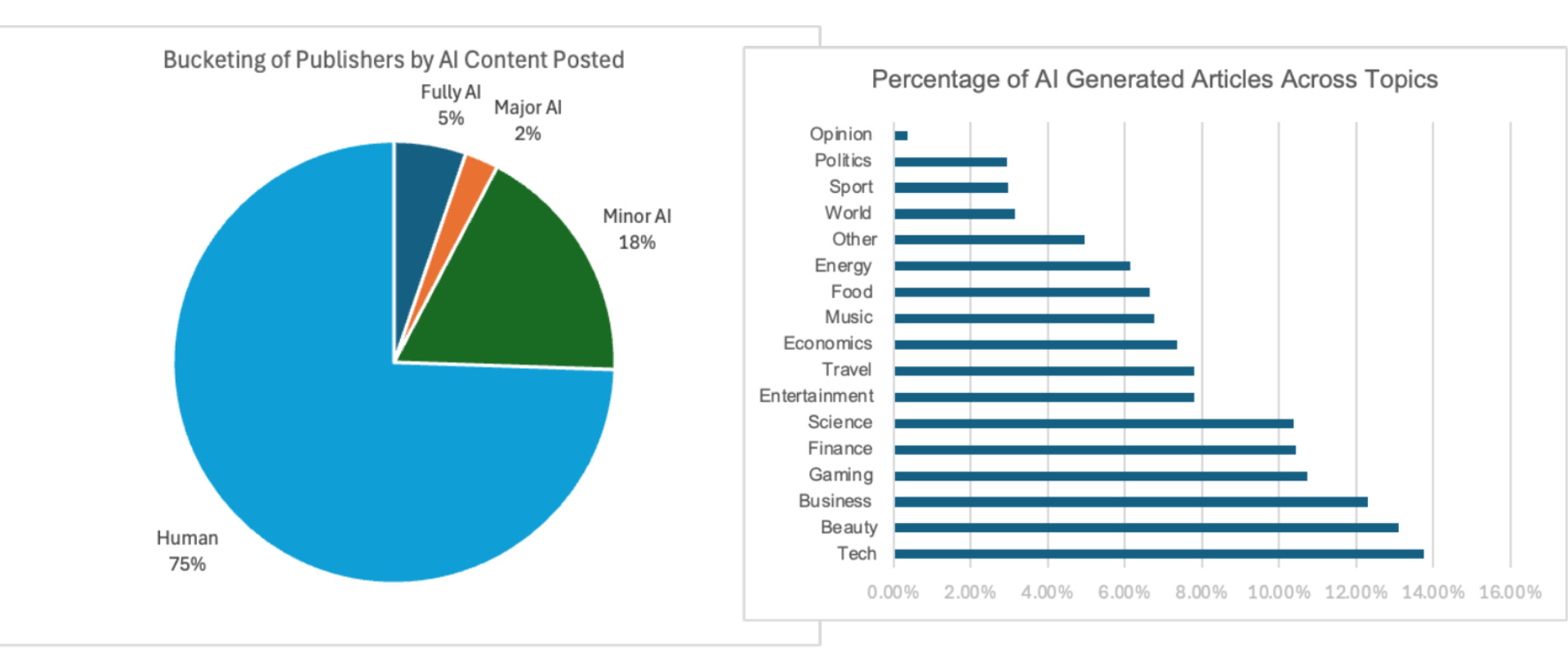

Add to this the way our media and information consumption has only increased in polarization since the onset of the pandemic and other national/global events, as well as the rise of AI slop and misinformation, and it makes more and more sense why you would want to distance yourself from people trying to manipulate you and focus only on your own instincts to make a decision or form an opinion. But it also sends the message that opinions or takes are bad.

But what if we tried something different: what if we cut the pretense that we can ever exist in pure, fact-based environments and acknowledge, respect, or even lean in to the fact that we are driven by worldview just as much as–if not more than–facts.

Here are some “facts” (ha) that seem to be true about our media consumption:

- We are more aware than ever that we are being manipulated

- We are busier and have less attention span than ever

Rather than a minimalist approach (ie, doing our best to root out an increasing tide of stuff we see as biased), we take a (curated) maximalist approach that can show us a range of interpretations that are closer to the reality of the world.

Especially, given the fact that we don’t have the time to stop and examine each issue, and often in a pinch seek out like-minded voices or perspectives to help us interpret things in real time.

This is why I love publications like Tangle so much.

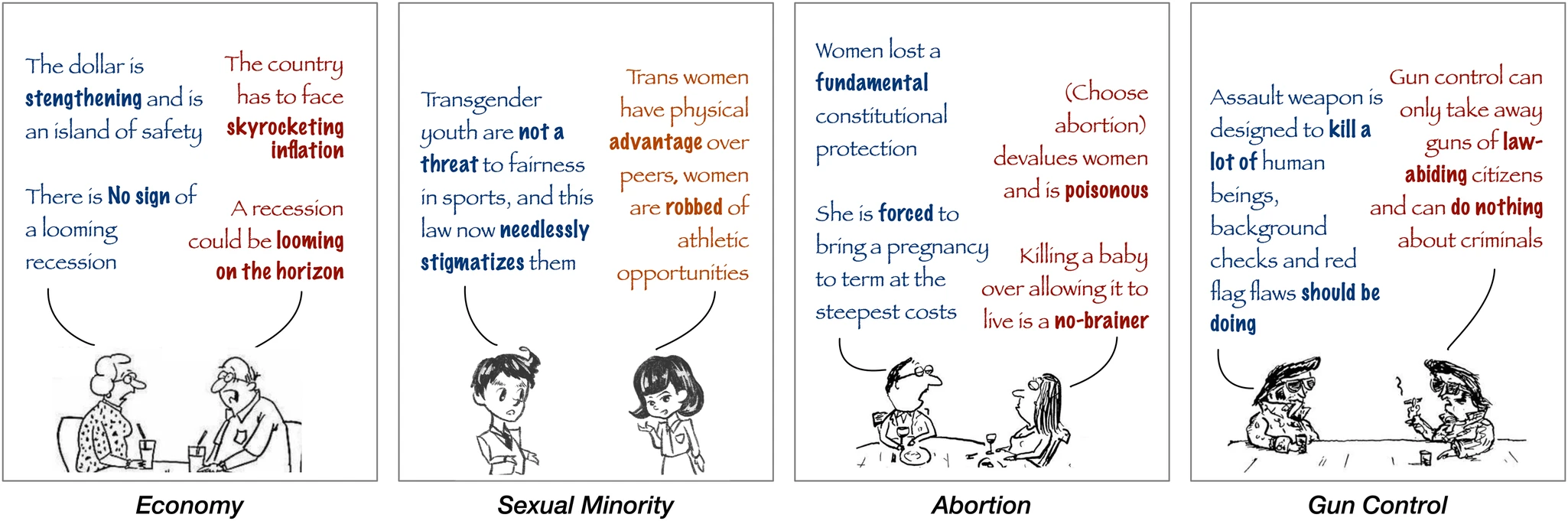

Each day in its newsletter it presents facts about a specific issue, but also a selection of editorial from left and right perspectives. It makes no claim to agree with the takes (unless Tangle’s Editor, Isaac Saul does in a special section that is only his opinion), but it also doesn’t deny that the takes exist, and more importantly that those takes are helping to form the opinions of thousands if not millions of folks across the country who are too busy or not as interested in exploring other sides.

Do I agree with what the “other” side is saying most of the time? Not usually. But I am always pleasantly surprised when I do. And at the very least it gives me nuance into why they think that. And reading publications like Tangle daily is a habit I have forced upon myself because I have become acutely aware that I am mostly guilty of interpreting things through my worldview.

This approach is refreshing and honest, and, most importantly for me, doesn’t view seeking others’ opinions as a failing. And I’m not sure where we got the idea that it is to begin with: is it some sort of individualistic American ideal? That we should be able to be intelligent enough to form our opinions and beliefs without our communities’ help?

To me, the act of seeking out opinions to help shape worldview is a higher form of independent thinking. And I think more people want it than they realize:

In one of our sessions with young people, we had them develop ideas for new news products. Among the many excellent ideas from the students, one of the groups pitched a lateral news consumption app that can help users do deep dives (side dives?), comparing multiple sources on a single news story in one unified experience.

We’ve learned from the faith community that discourse and comparing perspectives is not only common, but pivotal to deepening connection. From Machloket and Midrash in Judaism, to a run of books called “Four Views On” recommended to me by a local pastor in a listening session, we see that embracing, rather than excluding, editorializing can help us find meaning and connection with each other.

Where can we apply this kind of approach at a local level with news?

Many local newspapers have editorial sections or OpEd sections, but as we’ve noted before, more than 50% of people don’t know what the term OpEd means, and the makeup of those sections lead to people misinterpreting that as the paper’s stance, which leads to perceptions of bias in the paper.

What if we explored other ways to integrate human perspective into content, especially in local contexts?

One of my favorite sections in the (barely these days) satirical site The Onion is American Voices, where the paper has a sort of Greek Chorus of community members that sounds off on various issues or stories. The takes are of course hilarious and absurd, but the stories are sourced from reality.

What if local news and information sources had a diverse, trusted and responsible brain trust of community members who could weigh in on local issues to help viewers frame local issues? Not necessarily as a replacement for the two-way conversation of letters to the editor, but an expansion of that offering, and able to act as personas of thought across the ideological perspective, maybe even alongside reporting.

An approach like this could help honor the diversity of opinions in response to facts, but frame narratives free of national discourse, because as we’ve documented, polarization is lower at a local level. News and information (justifiably) stops short of offering opinions, but it also gives up on owning a space for dialogue and connection-building, things that are crucial for evolving the model into a tool that helps meet communities where they are: busy, inundated, and looking for trusted voices to help them make sense of an increasingly untrustworthy world.

Final adjective count: 118.

Oops, forgot to count “final”. 119.