There is a house I pass by on my walk to work almost every morning that has a chalkboard on its front door. On the board, in barely legible script, is usually a quote referring commentary about the current state of the world.

When Robert F. Kennedy Jr. dropped out of the presidential race and endorsed Donald Trump, the board listed RFK’s definition of what MAGA meant: “The phrase has troubled liberals who think it is a call for a return to an America before civil rights, gay rights, and women’s rights. But I have a more generous interpretation, one that is truer to my experience of Donald Trump as he is today. “Make America Great Again” recalls a nation brimming with vitality, with a can-do spirit, with hope and a belief in itself.”

In the aftermath of the October 7th attack in Israel, the board featured a quote from Golda Meir, “When peace comes we will perhaps in time be able to forgive the Arabs for killing our sons, but it will be harder for us to forgive them for having forced us to kill their sons. Peace will come when the Arabs will love their children more than they hate us.”

And so on.

You can probably glean the general politics of the resident of this house from these quotes alone. And for that reason, with it being situated right in the middle of a deep blue metro of Lancaster City, I’ve always been intrigued and curious to see what quote or thought would appear as the world turns, and with it, our community, on my walk to work each day.

Returning home in May of 2025, there was a short and simple quote scrawled on the board that I’ve been mulling ever since:

“You do not need proof for what people want to believe”- Thomas Sowell.

In googling the quote I found only a few references to it, though I suppose you could download 7 different wallpapers of it if you’d like from QuoteFancy, and it’s not even clear it was actually said by Thomas Sowell, a well known economist, political commentator, philosopher and Black conservative.

But still, as I continued my walk I found myself turning the phrase over and over in my head. I truly don’t know what the person in that house was referring to or thinking of when they put the quote on their board, but to me it set off a firestorm of examining what might be wrong about the way we’re talking about news and information in a post-fact age.

Since the creation and accreditation of the profession of “journalism” as a practice, the approach has largely been that the value of presentation of facts was self evident: a professional witnessed an event, or talked to someone who did witness it, and is now telling you what happened and maybe what it means in context of other events.

That the truth is the truth, regardless of what the audience might want to hear, and that in itself is all someone should need to believe it: because the person who is telling you that truth has credibility as a professional truth teller.

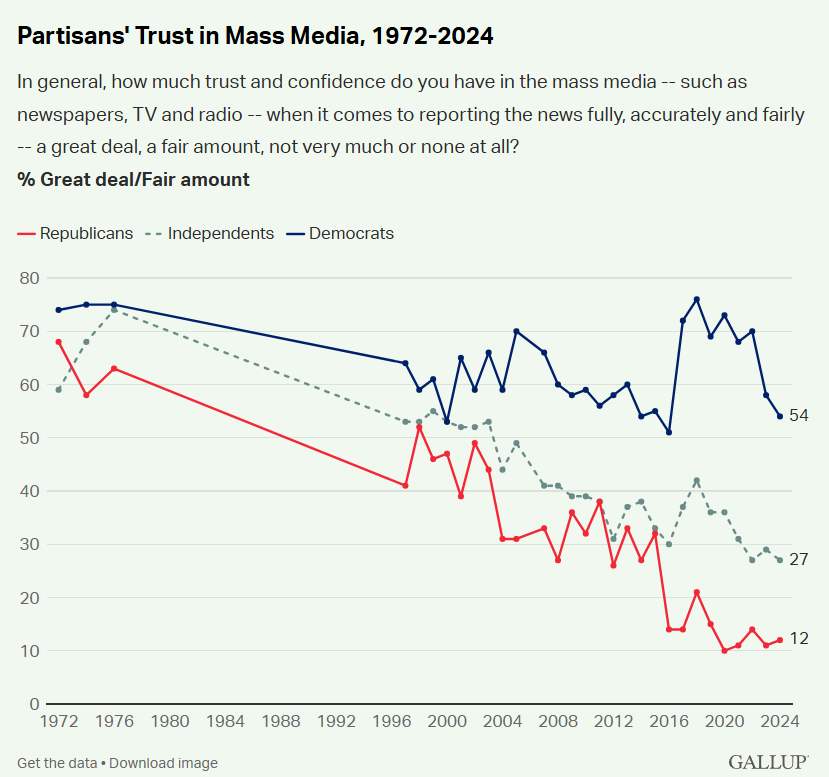

But, as we all know, that hasn’t been “true” in quite a while, maybe ever. And trust in journalism continues to decline, with just 31% of Americans expressing “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence in the media to report the news “fully, accurately and fairly,”. There is a partisan divide on this, but even among identified Democrats–a population that has traditionally been more trusting of journalism–there is a clear downward trend.

As our information consumption continues to fragment and become more siloed into our preferred worldview, “facts” no longer exist out of context. It’s true that they probably never did, but now we have loud and often obnoxious forces–whether it’s social media, in-groups, or even credible news outlets–that are hijacking the instinctual and lizard parts of our brain to think first and foremost with our worldview rather than our rational or critical thinking parts.

There is a very predictable and understandable desire in the journalism space to want to lead folks back to a place of critical thinking and trust: to get to a place of being able to believe hard truths when they are indeed truths, regardless of whether it aligns with what we want to be true, and regardless of how loud the forces spoon-feeding us reinforcement our worldview are.

I want that too. But I also don’t fully trust even myself to be able to do that all the time.

Why should we expect a busy, distracted, and siloed public to prefer to eat their brussels sprouts when there’s an endless supply of milkshakes available?

In fact, brussels sprouts were literally changed to become more palatable to consumers, if you believe it.

Back to the quote: “You do not need proof for what people want to believe.”

Taken as the inverse, it would be something like, “you’re going to have a heck of a time convincing people to believe things they don’t want to.”

But if we’re just giving the literal facts of the matter in a story, especially one that is presenting uncomfortable truths, it’s going to bump up against someone’s worldview. Guess which one is going to win most of the time?

It’s not really a surprise that information that is easier to digest with your worldview will make its way into believing the content more times than something that doesn’t.

The trap that I see news falling into more often than not however is the belief that just presenting the information as it exists is the only tool in their toolchest. And that if people won’t believe their reporting it’s a lost cause.

What if we approached news and information as a way to use this reality to our advantage? To not treat the consumers of our content as neutral ground, to understand, respect, or even embrace the fact that they are biased individuals shaped by a worldview, and utilized that as a tool for building trust?

Does that mean change facts to be more palatable like a brussels sprout’s DNA? Of course not. But maybe it means reminding someone that their father worked hard on cooking these brussels sprouts and would appreciate you at least trying them, because they’re good for you. This is definitely not a scenario about my kid.

A more direct example: conservative consumers of information might not be predisposed to believe or want to believe content talking about Donald Trump breaking the law. But could we start from a place of believing in the rule of law?

Progressive info consumers might not want to hear about a new report showing the efficacy of charter school vouchers. Can we start from a place of wanting our kids to have strong educational opportunties?

Instead of leading with just the information, maybe news sources should be cognizant of the fact that the consumers of said information will be primed with their worldviews, and work to account for that if they are trying to reach new or skeptical consumers.

This, of course, is not a situation where one strategy will fit all audiences. Instead, it calls for a potentially unsustainable level of customization based on audience, priorities, values, etc. It’s also not going to be as simple as using different words to create agreement on issues that have stark political divides.

And yet, if there were targeted efforts that sought to reach specific populations that started first with their respective worldview (what they “want” to be true), and working outward, what might we learn about the ways we’re sharing our information?

We’re intrigued by a project created by Braver Angels’ Sacramento chapter called Walk a Mile in My News, in which participants agreed to swap news feeds for a period of time, consuming the information, and also the beliefs, of that person.

Efforts like this are getting more to the root of the issue: building greater awareness for the importance of worldview in the ability for anyone to receive (or not receive) information, and expanding the journalistic toolbox to create ways for people to hold the tension of believing something they don’t want to be true.

But it’s also only scratching the surface of where I believe the real work is situated, which we’ve begun outlining in our recent Informed & Engaged report: going upstream from news as a concept to focus instead on better aligning our sense of shared humanity so that we can stand a stronger chance of receiving information that clashes with or challenges our worldview.

In short, helping us want to believe in each other.

What are some of the things that you “want” to believe, regardless of what information you might receive?