I–like many viewers of “prestige” television–have been enjoying The Pitt, for its realism, its PA-setting, and Noah Wyle’s resurgence in a white coat that perfectly scratches the millennial nostalgia itch I didn’t know was bothering me.

However, one recent scene seemed to truly violate the show’s Hippocratic oath to its viewers to do no harm, but in so doing I noticed a pattern that had been playing out in plain sight. And this pattern helped me see to the root of why so much reliable and trustworthy information can be met with skepticism or denial.

I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say that in a medical show set in an emergency depertment at some point someone dies. And along with that, Noah Wyle’s Doctor Rabinovitch must explain to a character that someone very important to them has done just that in a very unexpected/unplanned way. It’s an emotional climax to a very intense episode: you know the news that Wyle must break to this person, and you know the incredible time and effort that went in to trying to avoid this outcome. You are dreading the reaction from the character learning the fate of their loved one, and wish more than anything for it to be over as quickly as possible.

But of course, that’s not what happens.

Instead, Wyle takes us on a truly painful multi-minute recounting of the measures taken:

“[Character’s names]’s injuries were very serious. [They] stopped breathing. We were able to drain the blood that was collapsing [their] lungs.”

What?! I thought. Why would you mention that and give the person false hope that they had saved their loved one?!

Wyle continued: “We gave [them] as much blood as we could. We even transfused some of [their] own blood that was in [their] chest.

Again. This all sounds pretty…good? Why the wind up?

But we were unable to get ahead of the massive blood loss. [Their] heart stopped. We did everything that we could.”

And you can imagine what happened from there: tears on both sides of the TV, etc.

That scene frustrated me when I first saw it: why would you prolong this awful conversation by giving menial details–some of them seemingly positive–when in actuality this person just wants a simple yes/no answer to is my loved one okay?

It wasn’t until I started re-watching old episodes of ER (thank you MAX for the immediate suggestion on The Pitt’s title scroll) that I realized that this tactic wasn’t unique, I just noticed it more because of the heightened tension of the episode.

Time after time when it came down to giving bad news, the characters on the show (even baby Noah Wyle) never directly responded to “is my loved one okay?“, instead chronicling the journey of care towards the result.

The implication is clear: the doctors–or at least the ones they play on TV– can only effectively answer the question “is my loved one okay?” if they first answer the question “why should you believe me?“

A lot of information sources should take note.

To the viewer of a medical procedural, you witness most of a patient’s journey, including most meaningful interactions with the main character doctors, and the extraordinary steps they take to keep that patient alive.

From the family relation’s perspective however, things look very different: they come in with their loved one (if they were lucky enough to be with them) scared and unsure, see them taken behind doors, and then at some point a total stranger comes out to deliver an update, prognosis, or condolences.

Why wouldn’t you treat that interaction as important as this as a process of building a relationship and trust? If they simply delivered the bad news, even gently, it wouldn’t be enough. Explaining the steps taken isn’t just about documenting all measures taken, it’s helping the person getting the news understand that it’s trustworthy information. Telling the process of how you arrived at this result was just as important as the thesis, because without it, you don’t have enough information to trust the source.

When we think about the ways that news sources operate, how often are they delivering the news without the journey?

There is an incredible amount of work that goes into even the simplest, factual story at a credible news source. Some of it is easier to spot than others: an attributed quote implies that the reporter is getting information from people directly involved in the issue, or hyperlinks to other documents/stories can show context. But some of this process is more abstract and largely relies upon the public’s inherent trust that as a journalist this piece was written by someone acting in good faith, trained professionally, and writing with oversight.

That’s a lot of trust to assume without explaining the steps taken.

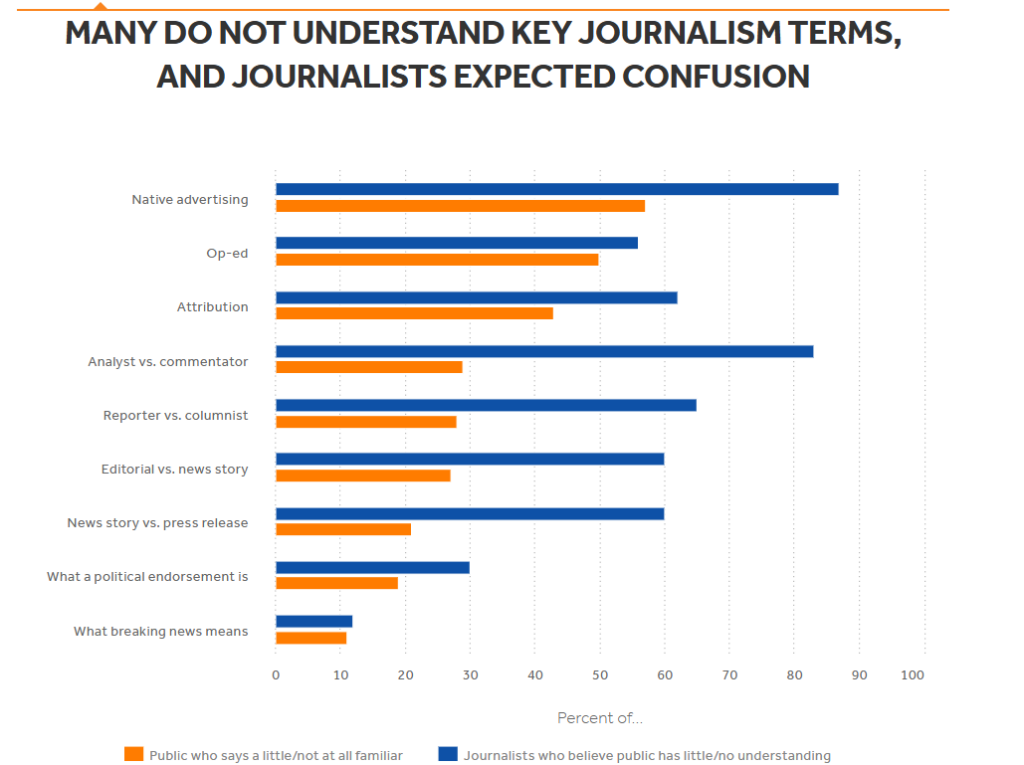

While I don’t advocate for documenting every minute detail of the editorial process a la Dr. Rabinovitch, I do believe that the journalism can’t afford to be passive in trust building with audience. A 2018 study from the American Press Institute found that:

- 50% of the public say they are only a little familiar with the term “op‑ed,” or don’t know what it is. Just 28% of people say they are highly familiar with the term.

- More than 4 in 10 adults (43%) say they don’t really know what the term “attribution” means in journalism, quite a bit more than the 30% who say they do understand that concept.

- 57% say they have little or no idea what the term “native advertising,” means, which is also known as “sponsored content” and refer to paid marketing content that resembles other editorial content in the publication.

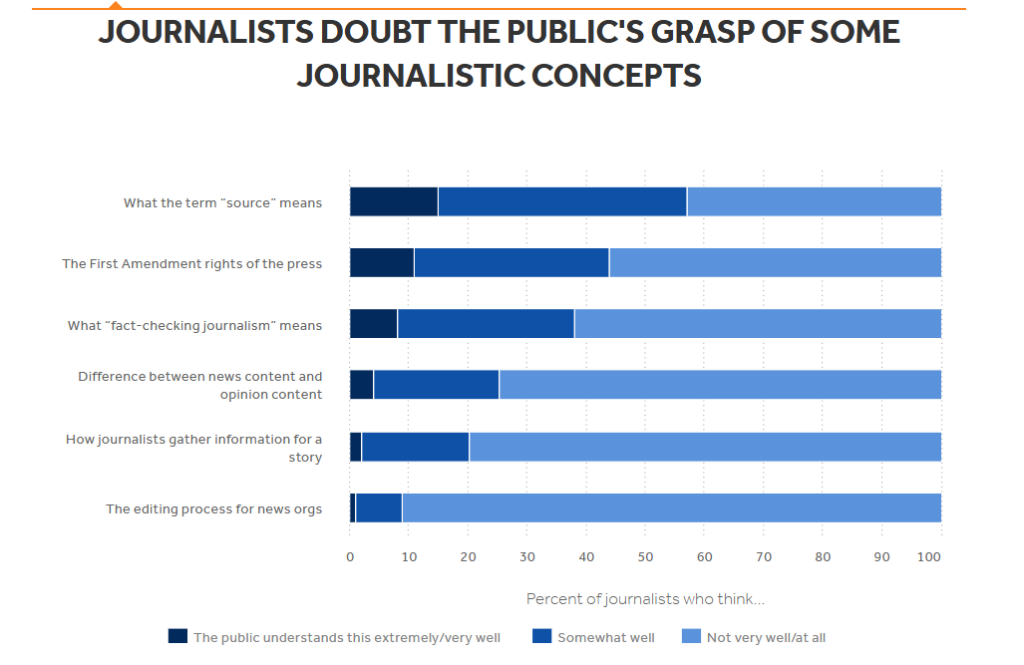

What’s more, the journalists surveyed don’t have much expectation of the public understanding their processes either:

And keep in mind, this was in 2018. Before the pandemic, before generative AI, and before YouTube content creators had truly become the leviathan of news and information sources that they are now, especially in sectors most skeptical of traditional media outlets.

So if the public is unaware/unclear on what steps we’re taking to make sure reporting is accurate, and journalists don’t expect them to anyway, why are we surprised that people are tuning out? Without process, people will either think reporting is biased because it doesn’t agree with their worldview, even if it’s fact-based or, the worse outcome: because they don’t know the difference between reliable and non-reliable sources, they believe it impossible to prove anything really is “true”, and self-select their choices out of comfort.

What are some ways we can work to tell the story without blitzing through wordcounts and boring people to death with process?

At the Steinman Institute, we are working on ways to increase transparency, trust, and public support for local news and information. We’ve seen through interviews, focus groups, workshops and pop-up community listening sessions that while people are divided along many lines (political, racial, cultural, geographic, etc.), there is real opportunity to build meaningful trust at a local level that can cut through the national narratives.

Even decisions as simple as having the reporter’s photo next to a story instead of an sterile signature can help build trust and embed an author in the community. While in the past, this may have been seen as self-aggrandizing, shunning anonymity and embracing authenticity help create lines of connection that can help the news you’re delivering be seen as trusted.

But what if we took it further? Maybe there are ways to show rather than tell process, to build trust. Take this prototype we threw together:

A simple tagging system could be implemented on stories to show all of the different aspects of work that went into the final product, while also increasing public knowledge of important terms of trade.

What’s more, if implemented consistently enough, it could have the effect of training users to even rely on them and be more skeptical of sources that don’t openly list their processes.

Eye-catching, intuitive and sortable features like this could also be adapted to overhaul news sections, which is surely needed as the API data shows far too much of the American people don’t understand the difference between editorial and the journalism sections of a news site.

These may seem like difficult changes from a software/tech stack standpoint, but it might not be as hard as you think. In fact, I quickly fed a local story through Google Gemini (I know, but I think this might be worth the bottle of water) and asked it to identify the journalistic practices used throughout, with text citation.

What came back to me was an impressive 9 page punch sheet of journalistic rigor: everything from direct quotes, to providing historical context, to using/citing direct data and statistics, to referencing previous reporting for readers to go deeper. You can read the full analysis here.

Might it be possible to have a process by which we can use analyses like this to highlight text or tag content based on practice when uploading to their respective website?

That all of this went into a single story might not be surprising to folks in the journalism space. But it might be astonishing to a casual reader who loves to throw cheap shots at reporting they didn’t do. The incredible work done by reporters every day is overshadowed by the perception that what they do is easy. And it’s up to the platforms, management, and processes of these outlets to help their reporters’ work shine.

Even though doctors (for the most part), are inherently trusted as experts in their field, they still go out of their way to explain their processes, methods and decision-making to build trust with their audience. They don’t take it for granted.

Why should folks in the journalism space? Doctors (again, for the most part), have a monopoly on attention and skillset: you can’t just go down the street and ask someone for an appendectomy (please don’t test this hypothesis THIS IS NOT MEDICAL ADVICE).

There are, however, any number of content creators willing to give you an opinion, hot take, or “cited” source that can prove whatever perspective they would like to promote.

Are these sources created equal? Of course not. But like it or not, reputable news and information is competing with them in a way that doctors aren’t. And the stakes are just as life threatening.